More Than Just Wi-Fi: What EMFs Really Are

When people hear “EMF,” they often think of Wi‑Fi or cell towers—things used for communication. But that is just one part of the story: Electromagnetic fields are created every time we use electricity. Not just in antennas or routers, but in everyday things like lamps, chargers, fridges, and even the wiring in your walls. These fields are a natural consequence of using alternating current (AC)—which is the standard form of electricity in homes. Unlike a battery’s direct current (DC), AC constantly changes direction which induces the EMF. Nowadays EMFs are everywhere where we live — also places we don’t intend them to be.

In fact, EMFs are not only created by technology—our own bodies produce them, too. The human body is an electromagnetic system. The brain sends electric signals across neurons. The heart emits rhythmic electromagnetic pulses. Cells communicate through electrochemical gradients and biophotonic emissions. Even between people, electromagnetic communication occurs – the heart’s field can be measured from a few feet away.

Living on earth, we are constantly exposed to natural EMF as well as part of geomagnetism and effects of the solar system and space, see Heliobiology. That’s why it’s essential to recognize that electromagnetic fields are not foreign to us—they are part of how life functions. We live within a natural electromagnetic field, and our biology both responds to and emits electromagnetic information. Certain EMFs, especially in biologically resonant frequency ranges, can support regulation and healing within the body. Other EMFs—particularly technological appliances with unnatural pulsations or chaotic waveforms—may disrupt these processes.

Importantly, not all man-made EMFs are harmful. In fact, when carefully tuned and applied, certain frequencies have been used in therapeutic settings for decades—like pulsed electromagnetic field therapy (PEMF), frequency-specific microcurrents, or bioresonance approaches. It’s not about EMFs being good or bad—it’s about understanding how different types interact with the body.

Where Are EMFs Found?

Wherever electrical energy is in use, electromagnetic fields arise as a by-product. Everyday appliances like lamps, kitchen machines, fridges, phone chargers, or even the cabling in walls generate EMFs simply by operating with electricity. In particular, most of our devices run on alternating current (AC), where the flow of electric charge reverses direction 50 times per second (in Europe). This continual switching creates oscillating electric and magnetic fields that extend into our living space.

Even if you don’t actively use electronic gadgets, your home wiring system itself radiates EMFs as long as it’s connected to a live grid.

Additionally, so-called dirty electricity—a form of high-frequency voltage transients—can “ride” on the electrical supply system. These disturbances often stem from dimmer switches, LED lighting or switch-mode power supplies. Once introduced, they can spread throughout the wiring of our power grid and contribute to the EMF load, whether or not those particular devices are currently in use.

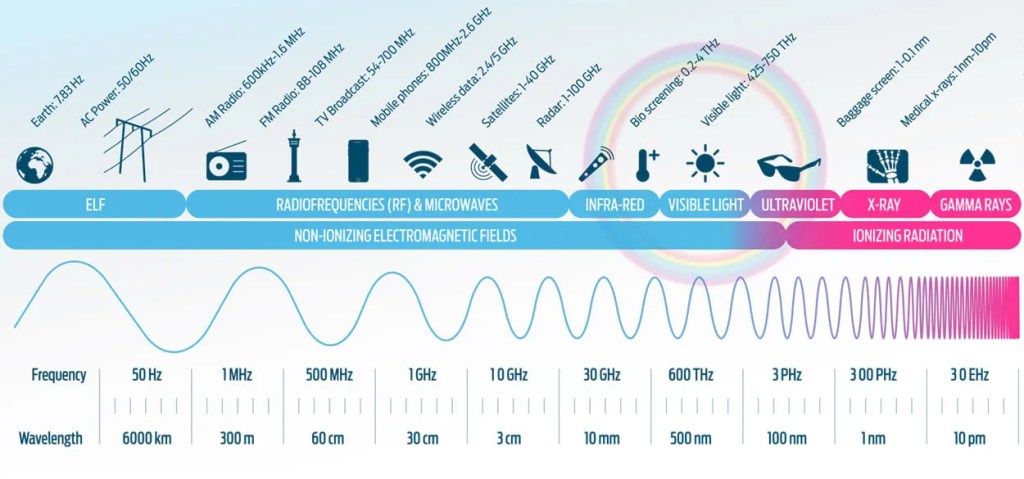

Electromagnetic Frequency Spectrum

Electromagnetic fields differ in frequency—that is, how many times per second the field vibrates. You can think of it like sound: a bass drum makes slow, deep vibrations (low frequency), while a violin string creates rapid, high-pitched ones (high frequency). In the same way, electromagnetic frequencies can be slow or fast, depending on how many cycles per second they produce—measured in hertz (Hz).

Let’s look at the most common types and their frequency ranges:

- 0–300 Hz (ELF): Extremely low-frequency fields from power lines, wall outlets, electric motors, electric blankets

- 2–150 kHz: Dirty electricity from dimmer switches, chargers, fluorescent or LED lighting

- 30 kHz–300 MHz (RF): Traditional radio frequency signals from baby monitors, walkie-talkies, older broadcast systems

- 300 MHz–3 GHz (Microwave): Wireless communication like mobile phones, Wi‑Fi, DECT phones, Bluetooth

- 3 GHz–300 GHz: Millimeter waves from 5G antennas, radar, military and satellite communications

Just like our ears react differently to various sounds, our cells may also respond differently to certain EMF frequencies. Some frequencies resemble natural rhythms found in the body, while others may have no biological equivalent or even may interact with tissues in disruptive ways.

Not Just About Heat: The Hidden Effects

Most safety guidelines focus on the heating effects of EMFs—whether the field is strong enough to raise body tissue temperature. This is especially emphasized in the microwave frequency range (e.g. mobile phones, Wi‑Fi), where energy can cause water molecules in tissues to vibrate and generate heat. But many studies now indicate that EMFs may affect us biologically even when no heat is produced at all. These so-called non-thermal effects have been shown to influence protein folding, oxidative stress, calcium signaling, and hormone regulation—even at very low exposure levels. You can read more about possible biological effects and underlying mechanisms in this summary.

Growing awareness of these effects is changing the conversation around EMF safety. It is not just about how powerful a field is, but how its signal quality and biological compatibility relate to our body’s own rhythms.

Scientific studies have raised key concerns through EMF exposure, including:

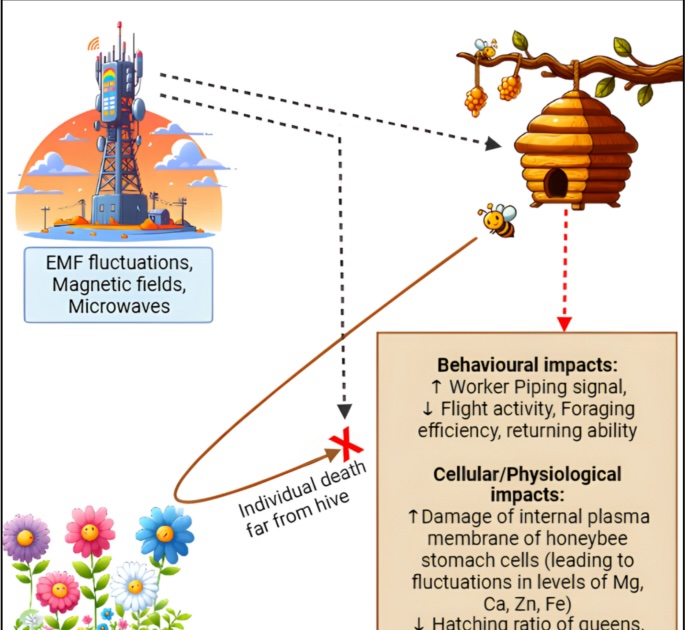

LEFT: Diagram showing how electromagnetic radiation from power lines and wireless sources may impact bee behavior and colony dynamics. Image source: SafeEMR.com

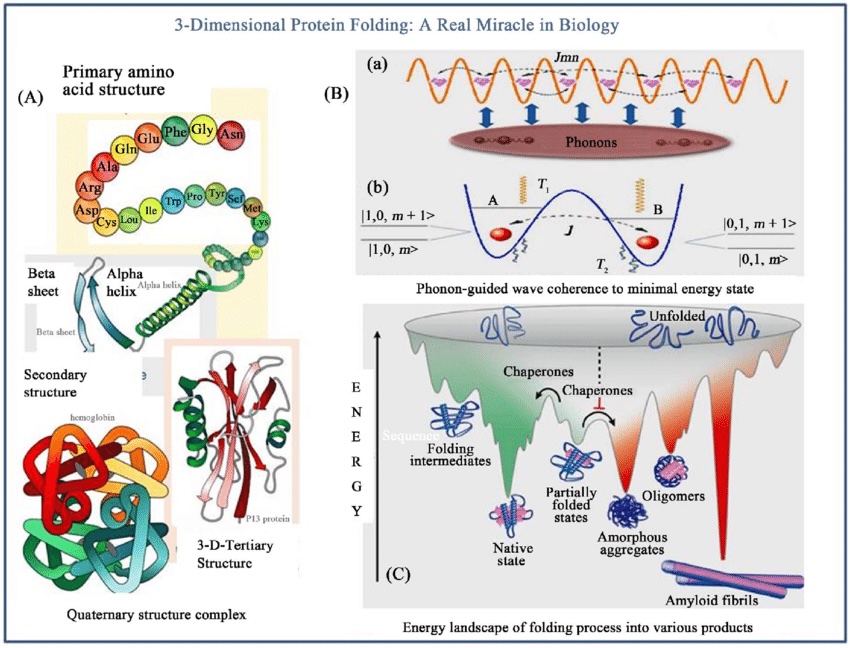

RIGHT : Illustration of protein folding processes and the influence of phonons (vibrational waves) in maintaining structural coherence. Image source: ResearchGate (Meijer & Geesink, 2018)

- Protein stability and denaturation

EMFs may interfere with how proteins fold, potentially impairing cellular function. - Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress

Pulsed fields and dirty electricity have been associated with increased free radicals and peroxynitrite formation—key markers of cellular stress. - Immune and metabolic disturbances

Research has shown improvements in multiple sclerosis, diabetes, and fibromyalgia symptoms when exposure to certain forms of dirty electricity was reduced. - Neurological sensitivity and developmental effects

Early-life EMF exposure is being explored as a possible contributing factor in neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder. - Autonomic nervous system dysregulation

EMFs may alter heart rate variability (HRV), stress protein production, and blood–brain barrier permeability. - Ecological impact on wildlife and plants

Observations show EMFs may disrupt orientation and reproduction in bees, birds, and livestock.

These effects aren’t yet fully understood, and cause-and-effect relationships are still being mapped. But the pattern is clear: EMFs can act not only as “heating” sources but also as informational triggers—subtle signals that cells may interpret as stressors.

All of this can happen at levels well below current safety limits. That’s why awareness is so important.

Healing with EMFs

For much of the last century, medicine has been shaped by the tools of biochemistry—focused on molecules, enzymes, and receptor pathways. This perspective has given us effective diagnostics and treatments, especially in acute and infectious diseases.

A patient using a pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) therapy mat for musculoskeletal healing. Image source: PainTherapyCare.com

But biology is not only chemistry. It’s also electricity, vibration, and light. Every cell generates voltage, every nerve transmits electrical impulses, and every organ is surrounded by measurable electromagnetic fields. Modern medicine is beginning to rediscover what early pioneers sensed: physics adds a deeper layer to understanding life—one that may help us detect imbalance earlier, support regulation directly, and work with the body’s own energy communication systems.

Historical Pioneers

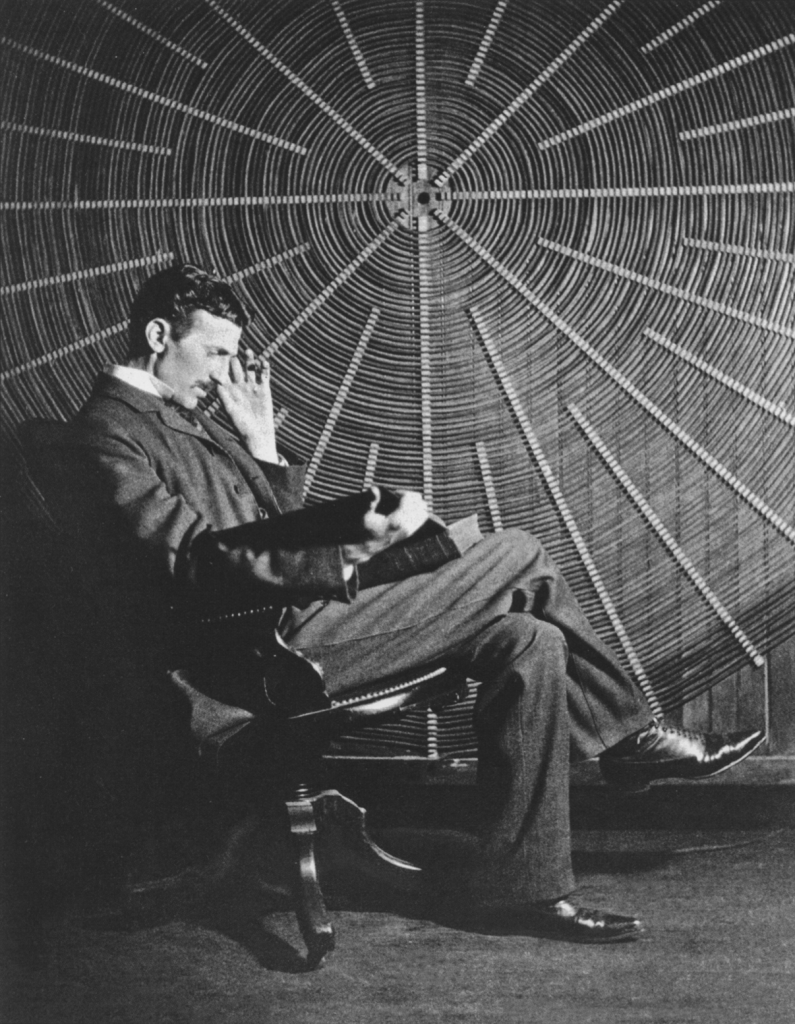

Nikola Tesla in his East Houston Street laboratory, seated before a Tesla coil; illustrating his work with high-frequency electromagnetic fields. Public domain (Wikimedia Commons)

Nikola Tesla (1856–1943), best known for inventing alternating current, also experimented with high-frequency electric currents and oscillating fields for biological effects. He proposed that energy, vibration, and frequency could play a central role in vitality and healing.

In the 1920s and 30s, Dr. Royal Raymond Rife developed one of the most powerful optical microscopes of his time, reportedly able to observe live viruses using special lighting techniques. Based on his observations, he built a frequency device—the “Rife Ray Tube”—designed to emit specific electromagnetic pulses to disable harmful microbes. Early trials in California were said to have promising results, but his work was not accepted by mainstream medicine and later fell into obscurity. Nevertheless, Rife’s idea—that diseases have frequency signatures that can be harmonized or disrupted—has inspired generations of researchers.

In the decades that followed, others expanded on these ideas.

In Europe, Dr. Paul Nogier introduced auriculotherapy and pioneered electroacupuncture using microcurrents to stimulate acupuncture points. Practitioners like Dr. Reinhold Voll and Franz Morell helped develop bioresonance techniques, which aimed to detect and rebalance disturbances in the body’s electromagnetic patterns. Their devices—such as MORA and later BICOM—sought to measure skin conductivity and respond with corrective frequencies.

From Past to Present – The Modern Revival

These pioneers laid the foundation for what’s now called energy medicine. Today, contemporary practitioners use a growing number of tools that build on these roots: frequency generators, pulsed field mats, photobiomodulation devices, and skin-conductance feedback systems. These are increasingly used in integrative and holistic practices to help regulate chronic illness, stress-related conditions, or nervous system disorders:

- Frequency-specific microcurrent systems apply precise low-level currents to reduce inflammation or stimulate tissue repair

- Photobiomodulation devices with infrared or red LEDs are used to enhance mitochondrial function

- Biofeedback-guided frequency devices scan the body’s responses and deliver harmonizing signals in real time

- PEMF mats are used to stimulate circulation and cellular energy in sports recovery and chronic pain

Energy Medicine adds another dimension: one that helps us understand the informational and vibrational side of health—the signals between cells, the rhythms of organs, and the fields that surround and organize our biology. When these systems fall out of sync, symptoms may appear—even before a chemical imbalance becomes measurable. Energy medicine offers tools to support these subtle systems: not by blocking or attacking, but by restoring inner communication and resonance.

Clearing the Confusion

There’s a lot of mixed information out there about EMFs. Some people feel overexposed and anxious. Others dismiss the topic entirely. Research presents a complex picture—some studies suggest possible risks, others show promising therapeutic uses. The result is often confusion and hesitation.

But EMFs are not automatically dangerous, nor are they simply neutral. They’re part of how both technology and biology work. Their effects depend on frequency, waveform, intensity, and context. Just like sound can be noise or music, EMFs can be dissonant—or harmonizing.

That’s why we need a new way of thinking: not fear-based, but informed. Understanding EMFs means recognizing their potential both to disrupt and to support health. It means learning how to reduce potential harmful exposures while making use of beneficial applications—especially those that align with the body’s natural rhythms.

By approaching EMFs with clarity and nuance, we can move from confusion to confidence—and begin shaping environments that support both modern life and human biology.